(All scientific sources referenced in this article are listed in the bibliography section at the end)

In a culture that rewards noise, self-promotion, and constant visibility, quiet confidence stands out as rare and magnetic.

It’s not about dominance or arrogance — it’s the steady equilibrium of self-assuredness that comes from genuine competence and emotional regulation.

While many online definitions of “alpha” behavior celebrate volume and control, psychological research consistently shows that sustainable influence arises not from aggression but from prestige: a form of status built on trust, skill, and generosity.

This article draws from behavioral science, social psychology, and leadership research to define the core traits of quiet confidence and the concrete steps any man can take to cultivate them.

1. The Prestige Path: Why Quiet Confidence Wins

Across cultures, status follows two evolutionary routes — dominance (control through fear) and prestige (influence through skill and respect).

Studies in evolutionary psychology show that people naturally grant social deference to those who demonstrate competence and prosocial behavior rather than intimidation.

Quietly confident men operate through the prestige pathway: they lead without noise. They listen more than they speak, teach more than they command, and inspire loyalty instead of fear. This subtle dynamic makes them far more trusted and stable over time.

Key takeaway: Confidence rooted in competence and generosity outperforms dominance-based behavior in both social and professional contexts.

2. Emotional Regulation: The Foundation of Presence

One of the strongest predictors of quiet confidence is emotional regulation — the ability to remain composed under stress.

Neuroscientific research shows that men who manage emotional reactivity demonstrate stronger prefrontal-limbic coordination, meaning they can think clearly even during conflict.

This composure conveys safety and authority to others. Leaders, partners, and peers subconsciously read calm emotional responses as indicators of control and reliability.

Practical step: Daily breathwork and mindfulness routines — even five minutes of slow, deliberate breathing — have been shown to improve emotional regulation and reduce physiological stress responses over time.

3. Competence and Continuous Mastery

Confidence without competence is an illusion — a fragile shell that collapses under pressure.

Studies on self-efficacy (Bandura, 1977) show that mastery experiences — not affirmation — are the core source of genuine confidence. High-value men don’t rely on external validation; their assurance comes from observable skill.

They seek to be capable, not just admired. Whether in a profession, a craft, or physical discipline, mastery builds internal proof that “I can handle this,” which quiets insecurity and produces genuine confidence.

Practical step: Focus on skill stacking — deliberate, consistent improvement in key domains that align with your goals or identity.

4. Measured Speech and Deliberate Communication

Psycholinguistic studies show that confident speakers use measured pacing, lower pitch variability, and concise language. Excessive verbal output often reflects anxiety or a need for approval.

Quietly confident men use silence strategically. They listen longer, respond thoughtfully, and speak only when they have something meaningful to add. This conversational restraint increases perceived authority and trustworthiness.

Practical step: Before responding, pause for two seconds. Speak slower and lower — it projects composure and control.

5. The Body Language of Stability

Body language research confirms that nonverbal cues — posture, eye contact, and movement — shape perception long before words are spoken.

While early “power pose” studies exaggerated these effects, replications found smaller but real correlations between open, relaxed posture and self-perceived control.

Quiet confidence appears in subtler signals: stillness, open palms, a relaxed jaw, and steady eye contact. The absence of fidgeting communicates certainty without aggression.

Practical step: Train “neutral openness” — shoulders relaxed, feet grounded, hands visible. Combine this posture with genuine awareness, not performance.

6. Social Calibration: Reading the Room

High-value men possess social attunement — the ability to read emotional cues and adapt behavior accordingly.

Research in emotional intelligence shows that individuals who can decode subtle facial and vocal signals navigate social hierarchies more effectively and are rated as more likable and trustworthy.

This calibration allows quiet confidence to stay balanced — assertive when necessary, but never overstepping. It’s what separates grace from bravado.

Practical step: After conversations, reflect briefly on tone, mood, and response quality. Calibration improves through intentional feedback, not performance.

7. Consistency and Behavioral Integrity

True confidence isn’t episodic; it’s consistent.

Behavioral studies on reliability show that people assess confidence not by charisma but by predictability — whether actions align with stated principles.

High-value men earn trust by showing up repeatedly, doing what they said they would, and remaining composed when conditions change.

Practical step: Under-promise, over-deliver. Consistency compounds reputation faster than self-promotion.

8. Humility and the “Quiet Ego”

Confidence and humility coexist naturally.

The “quiet ego” concept, developed in positive psychology, refers to individuals who are secure enough in their worth to prioritize learning, empathy, and self-growth over image maintenance.

This mindset produces calm self-assurance and interpersonal warmth — qualities consistently rated as more attractive and effective in leadership contexts.

Practical step: Ask for feedback, credit others, and view challenges as data, not threats. This cognitive flexibility strengthens authentic confidence.

9. Healthy Boundaries and Non-Defensiveness

Confident men respect both their own limits and others’.

Psychological boundary research connects secure self-concept with the ability to say no calmly and assertively — without guilt or hostility.

Quiet confidence expresses itself not through control, but through clarity: “This is what I can do; this is what I can’t.”

Non-defensiveness, too, reflects deep security — the ability to receive criticism without collapsing or retaliating.

Practical step: Practice short, clear statements of limits. Confidence doesn’t need justification — only consistency.

10. Prestige in Modern Masculinity

Quiet confidence is not passivity; it’s authority under control.

In modern society, dominance-based masculinity (loud, reactive, controlling) increasingly backfires — it’s misread as insecurity.

Prestige-based masculinity (calm, skilled, generous) commands deeper respect and social capital.

High-value men are those who embody competence and composure — men who don’t need to announce power, because it’s already evident in their stability and contribution.

Developing Quiet Confidence: A 3-Part Framework

1. Internal Regulation (Mind & Physiology)

- Breath control

- Regular physical training (especially resistance training for somatic grounding)

- Mindfulness and cognitive restructuring for emotional balance

2. External Competence (Skill & Presence)

- Identify and master 1–2 high-value skills

- Practice effective communication (measured, grounded, clear)

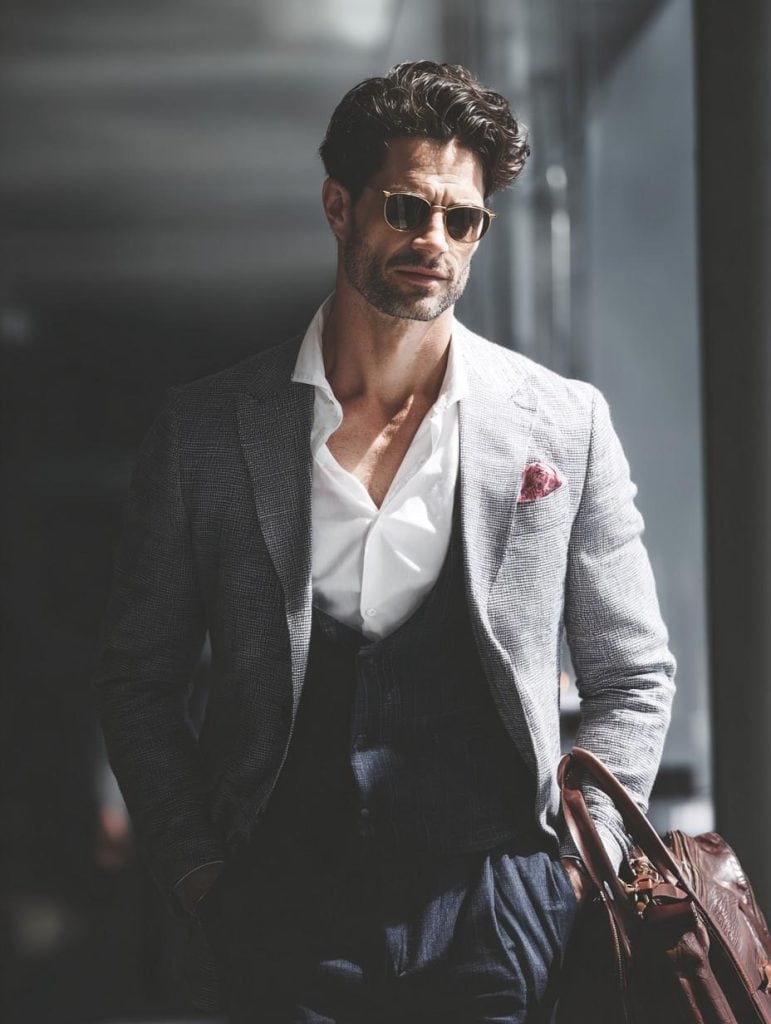

- Maintain posture and dress that reflect self-respect, not vanity

3. Social Calibration (Prestige & Integrity)

- Lead by teaching, not boasting

- Uphold consistent standards

- Be generous with knowledge and calm in disagreement

Conclusion: The Power of Subtle Strength

Quiet confidence is the convergence of competence, calm, and character.

It doesn’t demand attention — it attracts it.

Every trait that defines it can be cultivated: composure through emotional regulation, influence through mastery, and trust through integrity.

Men who carry themselves this way represent a new model of strength — grounded, gracious, and deeply self-assured.

And in a world flooded with noise, they are the ones who command attention without ever asking for it.

Bibliography

- Anderson, C., & Kilduff, G. J. (2009). The pursuit of status in social groups. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 18(5), 295–298.

- Bandura, A. (1977). Self-efficacy: Toward a unifying theory of behavioral change. Psychological Review, 84(2), 191–215.

- Cheng, J. T., Tracy, J. L., Foulsham, T., Kingstone, A., & Henrich, J. (2013). Two ways to the top: Evidence that dominance and prestige are distinct yet viable avenues to social rank and influence. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 104(1), 103–125.

- Gross, J. J., & John, O. P. (2003). Individual differences in two emotion regulation processes: Implications for affect, relationships, and well-being. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 85(2), 348–362.

- Henrich, J., & Gil-White, F. J. (2001). The evolution of prestige: Freely conferred deference as a mechanism for enhancing the benefits of cultural transmission. Evolution and Human Behavior, 22(3), 165–196.

- Keltner, D., Gruenfeld, D. H., & Anderson, C. (2003). Power, approach, and inhibition. Psychological Review, 110(2), 265–284.

- Liu, G., Ferrer, E., & Shoda, Y. (2019). Quiet ego and flourishing: A longitudinal study of humility and growth orientation. Personality and Individual Differences, 138, 249–257.

- Matsumoto, D., & Hwang, H. S. (2013). Nonverbal communication: The messages of emotion, social status, and power. American Psychologist, 68(3), 203–217.

- Neuberg, S. L., Kenrick, D. T., & Schaller, M. (2011). Human threat management systems: Self-protection and disease avoidance. Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews, 35(4), 1042–1051.

- Roberts, B. W., Walton, K. E., & Viechtbauer, W. (2006). Patterns of mean-level change in personality traits across the life course: A meta-analysis of longitudinal studies. Psychological Bulletin, 132(1), 1–25.

Tasos Moulios is the founder of Beardlong. He loves trying different beard and hair styles and blogs about them. The tips he shares come from his own experience and love for what he does.